|

| Photo courtesy of Keck Museum, UNR |

|

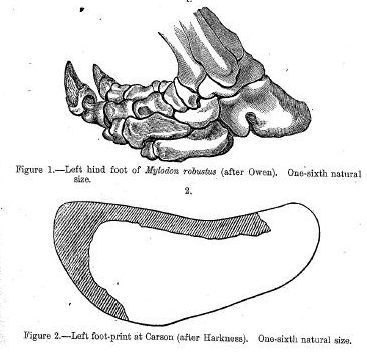

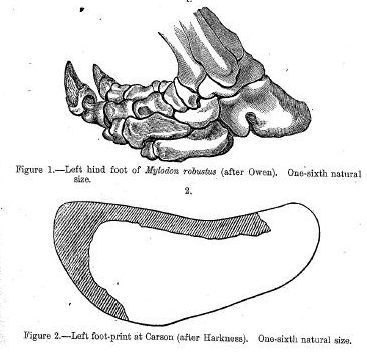

| MylodonGiant ground sloth foot and track |

|

| MylodonMylodon giant ground sloth |

The prints in question were approximately 18 to 21 inches long and 8 to 9 inches wide. Though bearing a superficial resemblance to human prints, the tracks lacked obvious digit impressions and normal heel-ball-arch bottom contours typically found in human prints--features that Harkness explained by suggesting the giant trackmaker might have worn sandals. However, besides the enormous size and lack of distinct human features, the tracks also showed an unusual gait pattern, with a wide trackway gauge of 18 to 19 inches but very short average pace length (for the size of the prints) of only about 2 and a half feet.

Within a year other scientists who studied the prints (LeConte, 1882, Davidson, 1883; Marsh, 1883) attributed them to a giant ground sloth named Mylodon, whose bones were found among other late-Pliocene to early Quaternary fossils in the same quarry. Further analysis was conducted by Chester Stock (1917, 1920, 1926) of the University of California, who carefully reconstructed a giant sloth foot and matched its imprint with the details exhibited by the prison tracks, confirming LeConte's earlier conclusion, and settling the matter even to the satisfaction of most earlier "giant track" advocates. Evidently giant ground sloths walked (or perhaps waddled is a better word) with weight on the outside of their feet, with the sole facing inward, and the claws pointing somewhat upward. This, along with the evidently soft nature of the mud when the prints were originally made, explained the lack of claw marks in the oblong prints (Eaton, 2005). Their generally bipedal appearance could have been due to either sloths walking on their hind legs, or the overlap of any fore prints with the hind feet--a phenomena known for a number of other prehistoric and modern animals. For example, some trackways of sauropods ("brontosaur" type dinosaurs) show only rear prints, or primarily rear prints, even though it is highly unlikely that any sauropods traveled in a bipedal manner. However, there were indications of fore-foot prints on some of the problematic tracks, indicating that the trackmaker walked on all fours at least at times, --further ruling out a human trackmaker (Davidson, 1883).

In recent years a few strict creationists (Ferrell, 2001; Jochmans, 1979) have attempted to re-encourage the human track interpetation. They emphasize the lack of claw marks and tail marks in the trails. However, they fail to mention the above explanations for the lack of claw marks, as well as the non-human gait patterns and evidence of fore prints. In regards to tail marks, the relatively short tails of ground sloths certainly would not touch during quadruped locomotion, and may not have touched while walking bipedally.

At any rate, virtually all mainstream workers and even most creationists have accepted the prints as probable giant ground sloth tracks. It should be noted that even if the prints were early humans or hominids, their size would be more problematic than their age, since the presence of hominoids in late Pliocene/early Quaternary strata is not in conflict with mainstream geology.

Some of the prints, along with photographs and diagrams of the quarry trackways, are housed at the W. M. Keck Earth Science and Mineral Museum at the University of Nevada, Reno. For those interested in further researching these tracks, a detailed bibliography has been compiled by the Nevada State Museum.

|

Eaton, Joe, 2005, "Ground SLoths May Have Roamed Prehistoric Berleley," Berkeley Daily Planet, July 12, 2000. Eaton comments: "Sloth tracks look oddly humanoid."

Ferrell, Vance, 2001, The Evolution Cruncher, Evolution Facts, Inc. On-line version of pertinent chapter: http://evolution-facts.org/Ev-Crunch/c13b.htm

Jochmans, Joseph R., 1979, Strange Relics from the Depths of the Earth (booklet). Forgotten Ages Research Society, Lincoln, NE, p. 17. Web version at: http://www.delusionresistance.org/creation/antedeluvian_finds.html

LeConte, J. 1882. On Certain Remarkable Tracks Found in the Rocks of the Carson Quarry. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Aug. 27th.

LeConte, J. 1883. Carson Footprints. Nature, Vol. 28, Pp. 101-102.

Marsh, O. C. 1883. On Supposed Human Foot-prints Recently Found in Nevada. American Journal of Science, Series 3, Vol. 26, Pp. 139-140.

Stock, C. 1917. Structure of the Pes in Mylodon harlani. University of California Publications, Department of Geology Bulletin, Vol. 10, Pp. 267-286.

Stock, C. 1920. Origin of the Supposed Human Footprints of Carson City, Nevada. Science Magazine, Vol. 51, No. 10325, Pg. 514.

Stock, C. 1936. Sloth Tracks in the Carson Prison, Westways, July, Pp.26-27.